Modulation

Tonicisation

Although this page is supposed to be about modulation, I'm going

to start with a much more interesting and immediately useful idea

called tonicization

.

This is probably the big payoff from music theory. I always used

to wonder why, and more importantly how, a composer chose to sharpen

or flatten a particular note in a harmony or a melody. That sharp

or flat was obviously not a member of the key that the composition

was in, nor did the piece obviously modulate (change key) at that

point. The answer in almost all cases was a technique variously

known as tonicisation

, borrowed chords

or what Piston

calls the Secondary Dominant Principle

. Rather than waffle

on any further, let's take a slightly modified example from Piston

to see how it works.

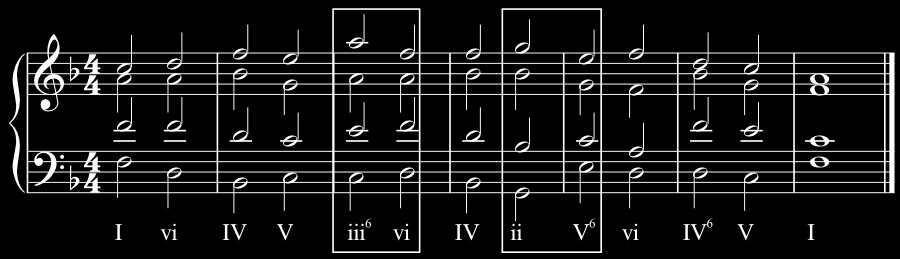

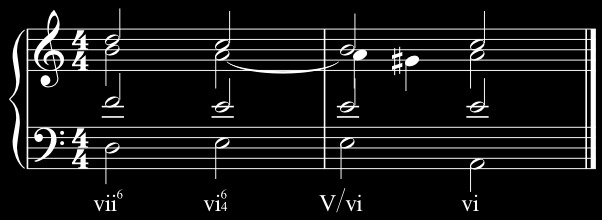

This short sequence is very much in the key of F major. Note that in the two boxes, the first chord stands in dominant relation to (a fourth below) the second, but in both cases the first chords are minor chords. If we make those chords major then they can act as true dominants to the following chord:

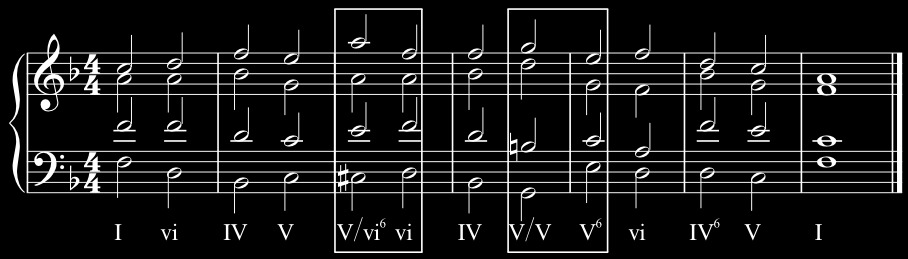

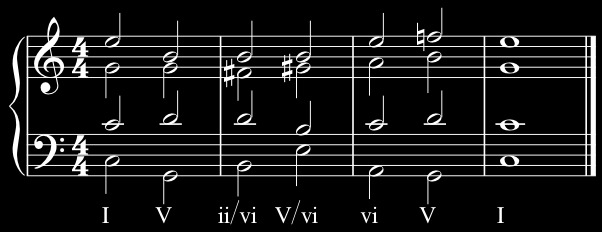

These chords are secondary dominants. They function

as dominants of the following chord. In fact the Secondary Dominant

Priciple states that any chord of a key may be preceeded by its

dominant.

Note also that the names of the chords have changed unexpectedly.

Instead of the major iii6 being written III6, which would be correct, it is written V/vi6 which gives a better idea of its function.

The /

is read as of

, e.g. V6 of

vi

(the 6

suffix applies to the whole

chord, so can be written last.)

Now these are not real modulations, since in both cases the piece continues in F major as if nothing had happened. In fact the chord IV in bar four has an F♮ and a B♭ that returns the key to F before the B♮ of V/V sets off in a new direction to the key of C. I have a rather colourful analogy that might help to visualise what is happening. It's rather like a speed boat going very fast. it is both pointing in, and travelling in, one direction (key). If the captain turns the wheel, the boat will start to point in a new direction but will not actually start to change direction yet. If the wheel is righted so that it points in the old direction again, then the captain has just made the journey a little more exciting without actually changing course.

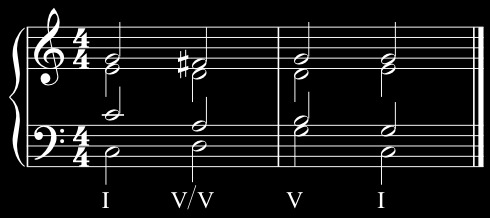

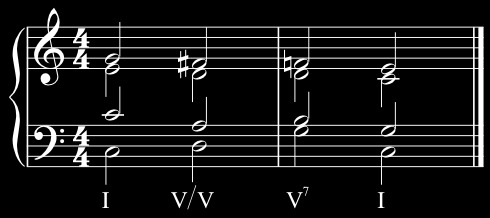

In many cases it is desirable to right the wheel very quickly after a tonicisation, by sounding the flattened leading note (third of the secondary dominant) as soon as possible. For example if the progression is V/V going to V followed by I:

then that final I sounds like IV/V. One common technique to rectify this is to replace chord V with chord V7, because the 7th of V is the flattened leading tone in the key of V:

Note that in this example the temporary leading tone, F♯ does not rise to the temporary tonic G but instead falls to the

flattened seventh F♮ as part of a familiar chromatic

sequence known as a Barber Shop

progression.

The Extended Secondary Dominant Principle

If the Secondary Dominant Principle ended there, it would still

be a neat trick, but it would only give you one new chord to try

at any particular point. In fact it goes much deeper. What Piston

calls the Extended Secondary Dominant Principle

I like to

think of as the Secondary Cadence Principle

. The Secondary

Dominant Principle states that you can preceed any chord of a key

with its dominant. The Extended Secondary Dominant Principle says

that you can preceed any chord of a key with a cadential sequence

that targets it!

This means that everything you know about cadences can be applied, in principle, to these secondary tonics. Not all of the results will sound good, but the options become almost limitless. Here's just a few examples.

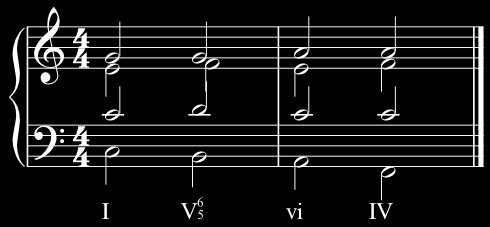

False Cadences

A false cadence occurs when a dominant resolves irregularily, that is to an unexpected chord. The most common false cadence is from V7 to vi:

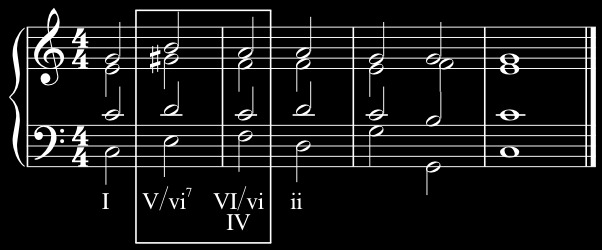

The V65 (V7 in first inversion) sets up a strong expectation that the next chord will be I, but instead chord vi follows. Now secondary dominants also set up a strong expectation that the following chord will be their secondary tonic, and we can pull the same trick there:

Chord V/vi7 expects to be followed by vi but instead we follow with VI/vi (which is also IV—remember that because vi is minor, its submediant in the natural minor scale is major).

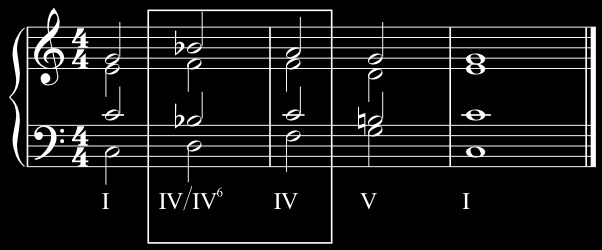

Plagal Cadences

You could call these Secondary Subdominants

and they work

pretty well when they introduce a note outside of the key:

Cadential Sequences

You are not restricted to just a single chord in a tonicisation. All the common cadential formulae can be applied. For example the cadential six-four:

The common ii, V, I sequence, applied to vi:

Secondary Dominants

Yes, that's not a missprint. The secondary dominant principle can be applied to sequences derived from the extended secondary dominant principle, so we can write sequences like V/V/vi (five of five of six) going to V/vi:

I can only provide a few random examples of the possibilities here. You really should experiment on your own, finding out what kinds of things work well for you. Hopefully this short blog has given a few of you some new ideas about writing music.