The Basics

I have to make a few assumptions about my intended audience here: I assume you can read music, I assume you know what an interval is, and that you know about major and minor scales. Other than that I'll attempt to cover the basics right up front then get quickly to the interesting stuff.

Triads

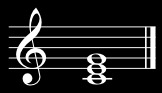

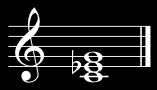

First off, the simplest chords are called triads, because they are made of three notes a third apart from one another. We can form a triad from any note by adding two notes a third and a fifth (3 plus 3 does equal 5) above it. Here's a triad built on C.

It's a major triad because the interval from C (the root) to E (the third) is a major third. If we flattened the E to make E flat, then it would be a minor triad:

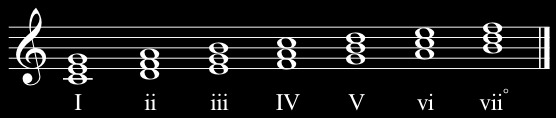

Like I said, you can form a triad on any note. Here are all the triads that you can make from the notes of C major:

Notice the roman numerals. Musicians use roman numerals to identify the chords of a key. It's useful because they are independant of the key itself, and so easier to transpose into other keys. The triad built on the first note of the key (C in this example) is given the number I, and so on. Beyond the simple use of roman numerals thare are many alternative and somewhat conflicting conventions. The one I've chosen is to use upper case roman numerals to indicate the major triads, and lower case to indicate the minor ones. The circle superscript of chord vii indicates it is a diminished triad, made up of two consecutive minor thirds.

This pattern of ascending chords: major, minor, minor, major, major, minor, diminished is common to all major keys.

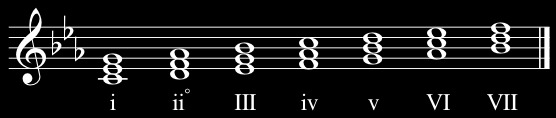

Minor keys are different. The natural minor scale shares the same notes as the major scale a minor third above, so we have the same sequence of chords as a major key, but starting six chords in (or three chords back).

The harmonic minor scale has a raised seventh. As the name suggests it is used for harmonizing melodies in minor keys:

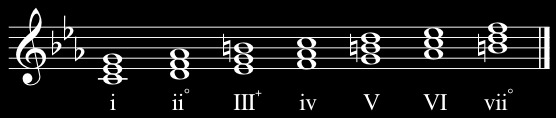

The raised seventh is to make chord V major, because an authentic cadence (V followed by I) needs chord V to be major. But this also affects chords III and vii: vii becomes diminished and III becomes augmented, signified by the "+" superscript: III+. An augmented triad is formed of two consecutive major thirds.

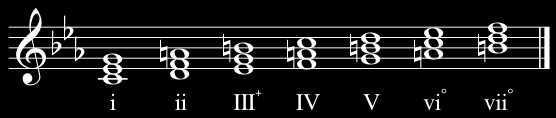

a melodic minor scale sharpens the sixth and seventh degrees when ascending, and flattens them when descending. The descending form of the melodic minor is therefore the same as the natural minor which we've already seen but the ascending melodic minor produces new chords:

You can see that compared to the harmonic minor, the additional raised sixth makes ii minor instead of diminished, IV major instead of minor, and vi diminished instead of major.

Apart from roman numerals, an alternative scheme which you should also be aware of is that each note of a scale and hence each chord rooted on that note and each key based on that note has a name. Here they are:

- I Tonic

- the "home" of the key

- II Supertonic

- The note/chord/key above the tonic

- III Mediant

- Half way between Tonic and Dominant

- IV Subdominant

- The same interval below the tonic as the Dominant is above (a perfect fifth)

- V Dominant

- The most important note/chord/key after the tonic

- VI Submediant

- As far below the tonic as the mediant is above

- VII Leading Note

- This note "leads" to the Tonic. It can be called Subtonic by analogy with Supertonic, but only if it is rooted on the minor seventh above the tonic (natural minor scale.)

Inversions

The notes of a triad can be rearranged so that different notes are in the bass. These are called inversions.

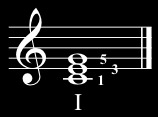

When the first note of the triad is in the bass, like all the chords we have seen so far, the chord is said to be in root position:

This chord, if it is the key of c major, can be written I53, meaning it is the notes of the tonic chord arranged so that there is a fifth and a third from the bass. But since thirds are taken as read, it is more usually written as just I.

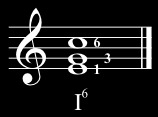

If the third of the triad is in the bass, we have what is called a first inversion:

Because this chord has a sixth and a third above the bass, it can be written in full as I63, but again thirds are taken for granted so it can be abbreviated to just I6.

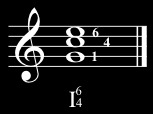

Unsurprisingly, if the fifth of the chord is in the bass, we have a second inversion:

This chord has a sixth and a fourth above the bass and is written I64, no shorthand allowed. I guess it could be written I4 with the third above the fourth implied, but I've never seen that.

This odd convention of a stack of numbers alongside the roman numeral of the root may seem unnecessarily complicated, since it is saying "the notes of such and such a root triad rearranged so that these intervals are above the bass". They actually come from an old style of musical notation called figured bass where the composer would write out the melody and the bass line in full, but would then write these numbers under the bass line to indicate to the keyboard player which chords they should be playing. In that case the numbers (without roman numerals) did indicate the intervals above the given bass note. But when that numbering was carried over into harmonic theory, the root of the chord was considered (rightly) much more important than the bass note of the chord, and so we have this rather counter-intuitive naming system that you just have to get used to.

Seventh Chords and their Inversions

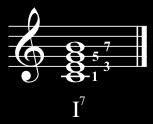

If you add the seventh from the root to a triad, you get a seventh chord:

Different chords of the scale have different sevenths. For the major scale, they are

| Chord | Seventh |

|---|---|

| I7 | Major |

| ii7 | Minor |

| iii7 | Minor |

| IV7 | Major |

| V7 | Minor |

| vi7 | Minor |

| vii7 | Minor or Diminished |

Notice that V7 is the only major chord of the key with a minor seventh. This means it is a defining chord of the key. In fact since it contains both the fourth and the seventh degree of the scale, this so-called Dominant Seventh unambiguously defines the key. For example in the key of C, the Dominant seventh consists of the notes G, B, D and F. The B♮ means we cannot be in a flat key, because B♭ is the first flat, and the F♮ means we cannot be in a sharp key, because F♯ is the first sharp.

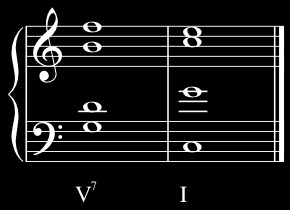

The Dominant Seventh is the most common seventh, and the progression of dominant seventh to tonic is the strongest progression in Western tonal music:

You may be thinking Chord vii also contains those notes, and you're right, however if we choose the diminished seventh of vii (which usually sounds better than the minor seventh) then we have a chord completely composed of consecutive minor thirds, and that chord can be the viio7 of four separate keys (this is useful in modulation, discussed later).

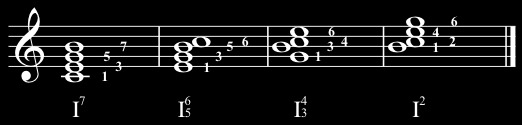

Because there are four distinct notes in a seventh chord, there are three inversions, as well as root position:

Using I as an example, the root position is just written I7, as the 3 and the 5 are taken as read. Likewise the first inversion is I65, the second inversion is I43, and the third inversion just I2. There is a useful mnemonic sequence to remember these: 7, 6-5, 4-3, 2.

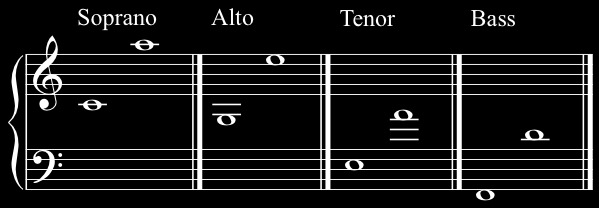

Four Part Harmony

Music theory, for the most part, deals with the interaction of four separate "voices" called Soprano, Alto, Tenor and Bass (S, A, T, B). They are written on two staves, the Soprano and Alto in the upper stave with a treble clef, and the Tenor and Bass in the lower stave with a bass clef. Their ranges are roughly as follows:

Although the ranges overlap, it is conventional that for any

given chord the four voices stack

with the Soprano on top,

the Alto below the soprano, The Tenor below the Alto and the Bass

on the bottom. Here's an example of four part harmony:

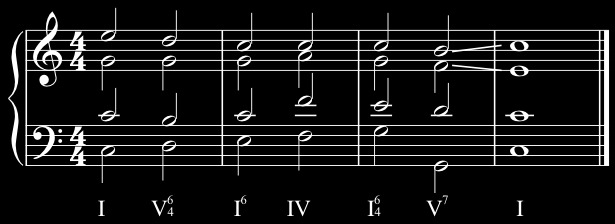

That very simple progression demonstrates quite a lot of the

rules

of harmony, rules that you need to know even if you

intend to break them later on. I need to lay down one really important

rule first, then we can examine that progression in more detail.

The rule is:

- Avoid parallel octaves and fifths at all costs.

Parallel octaves and fifths occur between two voices, an octave or a fifth apart, when they both move in the same direction by the same interval. They are especially evil when they occur between the Soprano and the Bass, but should be avoided in all cases.

Now back to our progression. First of all notice that there is often quite a gap betheen the Bass and the Tenor. This is normal and desirable to get a convincing bass line. Let's discuss each chord in turn, and consider its relation to its neighbours.

- I

- The tonic chord in root position. Notice that the Soprano,

Alto and Tenor notes are spread out rather than close together.

This is called

open position

. Their positions are not arbitrary though: they occur as E, G and C (top to bottom) This is the same order as they would appear in a first inversion triad read bottom to top. Put another way, you can get from open toclose position

(where the notes are as close together as possible) by transposing the Tenor up an octave. Another thing to note is that it is only the Bass of the chord that counts when identifying the inversion of the chord - the S, A and T can appear in any order. - V64 (open position)

- While root position and first inversion chords can be used

pretty much anywhere, the second inversion has more limited uses,

and this is one of them. It is called a

passing 6-4

and is placed so that its bass is on the note between the bass of a root position chord (I) and its first inversion (I6). - I6

- Here's a basic rule:

don't double the third in a major 6-3 chord

. There is a reason for this. Any major chord really wants to be a dominant, in which case the third acts as the leading note and wants to rise by step to the imaginedtonic

in the next chord. This tendancy is most pronounced if the third is in the Bass. If you were to double the third, you would have two thirds both wanting to rise by step and parallel octaves would result. For that reason what might have been an E in the Tenor has been moved down to the C, so the chord is neither in open nor close position. - IV (close position)

- This chord is often used to prepare an authentic cadence (V-I or I64-V-I).

- I64 (close position)

- This is the other main use of a 6-4 chord, as a

cadential 6-4

where it preceeds the dominant in an authentic cadence. This highlights why 6-4 chords are more awkward to deal with. They behave like adouble appogiatura

where both the 6 and the 4 want very much to resolve downwards by step to the 5 and the 3 on the same bass. I64-V does just this. Unless cleverly hidden (such as in a passing 6-4) almost any other chord following a 6-4 will sound wrong in some way. Also notice how the progression I V64 I6 IV I64 forms a scale. A smooth Bass is a sign of good four part writing. - V7 (close position)

- Since it follows a cadential 6-4 it has the same bass note, but here the bass drops an octave for a more final effect. Notice that the third (B) rises to the tonic (C) while the seventh (F) falls to the mediant (E) in the next chord. Again, to allow these natural progressions, the following chord is in neither open nor close position.

- I

- As discussed, the progression V-I at the end of a phrase constitutes an authentic cadence. If

furthermore both chords are in root position, and the Soprano of

the I is the tonic, then this is a

perfect cadence

. Many people mistakenly refer to any authentic cadence as a perfect cadence, but there is a difference.

Don't be fooled into thinking that this is just theory

-

good four part harmony can stand on its own as a finished piece of

music, and it forms the skeleton of most if not all tonal music

that has ever been written.

Voice Leading

The idea that certain notes have a natural tendancy to move to

others is called voice leading

. So far we have only seen the

leading note rising to the tonic and the seventh of the Dominant

Seventh falling to the third of the tonic. There are a few others

and if you want your music to flow, you would be wise to let these

notes do what they want to do.